Pope wraps up Mongolia trip, says Church not bent on conversion

World

Mongolia has only 1,450 Catholics in a population of 3.3 million

ULAANBAATAR (Reuters) - Pope Francis on Monday wrapped up a historic trip to Mongolia whose main purpose was to visit the miniscule Catholic community but which took on international connotations because of his overtures to China over freedom of religion in the bordering communist country.

Francis ended his five-day visit with a stop to inaugurate the House of Mercy, a multi-purpose structure to provide temporary health care to the most needy in the Mongolian capital as well as to the homeless, victims of domestic abuse and migrants.

Situated in a converted school and the brainchild of Mongolia's top Catholic cleric, Italian Cardinal Giorgio Marengo, the House of Mercy is destined to serve as a sort of central charity coordinating the work of Catholic missionary institutions and local volunteers.

"The true progress of a nation is not gauged by economic wealth, much less by investment in the illusory power of

armaments, but by its ability to provide for the health, education and integral development of its people," Francis said at the house.

He said he wanted to dispel "the myth" that the aim of Catholic institutions was to convert people to the religion "as if caring for others were a way of enticing people to 'join up'”.

Mostly Buddhist Mongolia has only 1,450 Catholics in a population of 3.3 million and in an unprecedented event on Sunday, just about the entire Catholic population of the country was under the same roof with the pope.

Mongolia was part of China until 1921 and the pope's trip was dotted by allusions or appeals to the superpower next door, where the Vatican has scratchy relations with the communist government.

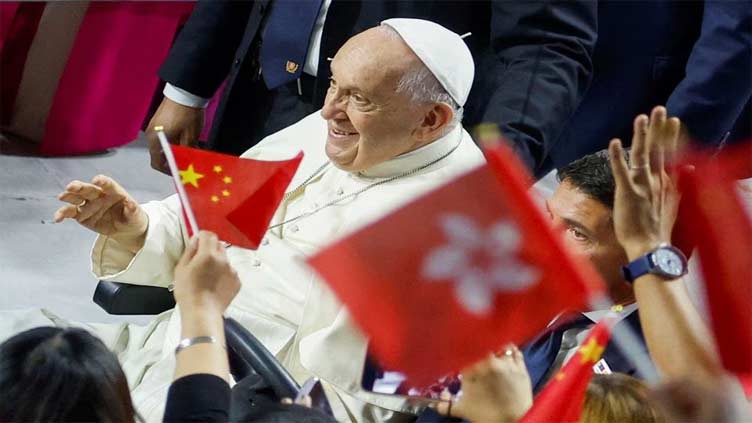

At the end of Sunday's Mass he sent greetings to China, calling its citizens a "noble" people and asking Catholics in China to be "good Christians and good citizens."

On Saturday, in words that appeared to be aimed at China rather than Mongolia, Francis said governments have nothing to fear from the Catholic Church because it has no political agenda.

Beijing has been following a policy of "Sinicisation" of religion, trying to root out foreign influences and enforce obedience to the Communist Party.

China's constitution guarantees religious freedom, but in recent years the government has tightened restrictions on religions seen as a challenge to the party's authority.

In December, the United States designated China, Iran and Russia, among others, as countries of particular concern under the Religious Freedom Act over severe violations.

A landmark 2018 agreement between the Vatican and China on the appointment of bishops has been tenuous at best, with the Vatican complaining that Beijing has violated it several times.

The phrase used by the pope on Sunday - "good Christians and good citizens" - is one the Vatican uses frequently in trying to convince communist governments that giving Catholics more freedom would only help their countries' social and economic progression.