On his 61st death anniversary, Manto lives on

Manto died at the age of 42 but Urdu language has never had a more controversial writer than him

LAHORE: (Web Desk) – Saadat Hasan Manto was born on May 11, 1912, in Ludhiana, Punjab in British India. He was probably the most controversial writer Urdu language has seen. Though his genre was short story only, Manto certainly had a grip on other genres of Urdu literature as well. He wrote one novel, 5 series of radio plays, 3 collections of essays, 2 collections of personal sketches and a series of letters to ‘Uncle Sam’, an imaginary character who Manto addresses as a representative of the United States of America (USA), calling himself (representing Pakistan) as his nephew.

But who was Manto? A rebel? A progressive? A universalist? Who was he? Let’s explore Saadat Hasan Manto.

A rebel NOT born

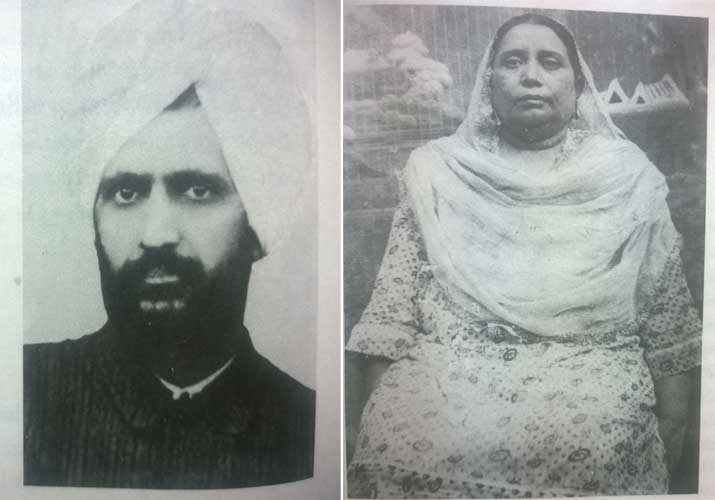

In his early life, Manto didn’t really have a childhood that a child would dream for. His mother Sardar Begum, who he used to call Bibijan, was the second wife of his father Khwaja Ghulam Hasan. A lawyer by profession, Khwaja Ghulam Hasan could never really convince his family to put Sardar Begum into same esteem as the other women of the family. The reason, of course, was that Sardar Begum was Ghulam Hasan’s second wife. Besides, she was not from the Manto clan, the first outsider in the family. Therefore, Manto lived along with his mother and sister Nasira Iqbal in a corner of the house and was never able to enjoy the prestige in the family that he and his mother deserved.

Manto s parents: Ghulam Hasan Manto and Sardar Begum

Ghulam Hasan wanted to get them the love that they must have received from the family and for this purpose he wanted Manto to study like his other sons, from the other wife. Two of those sons were doctors while one was engineer. Manto, on the other hand, did not like the Science subjects. He failed thrice to pass the school leaving exam and when he passed it eventually in the fourth attempt; he did it with languages, Urdu and Persian. There too, he failed in Urdu, the language of which he is one of the most revered writers today.

Manto thus developed complexes in his mind at a very early age. A highly sensitive boy, he felt the things around him so deeply that other boys of his age would hardly do. The traumas he had to go through in such a short life were unbearable for him. His sensitivity became his biggest enemy.

He never complained. He hated people who complained. He didn’t even like Pakistanis complaining about India diverting the rivers to damage Pakistan’s agriculture back in late 1940’s and early 50’s. His story ‘Yazeed’ is a clear example. The protagonist in the story tells people not to badmouth about India since India was an enemy, not a friend. He told them to think of ways to get their water freed from the enemy, instead of venting the anger out cheaply through abusing. Yes, he was a rebel; but a rebel with a cause.

The land route to Moscow

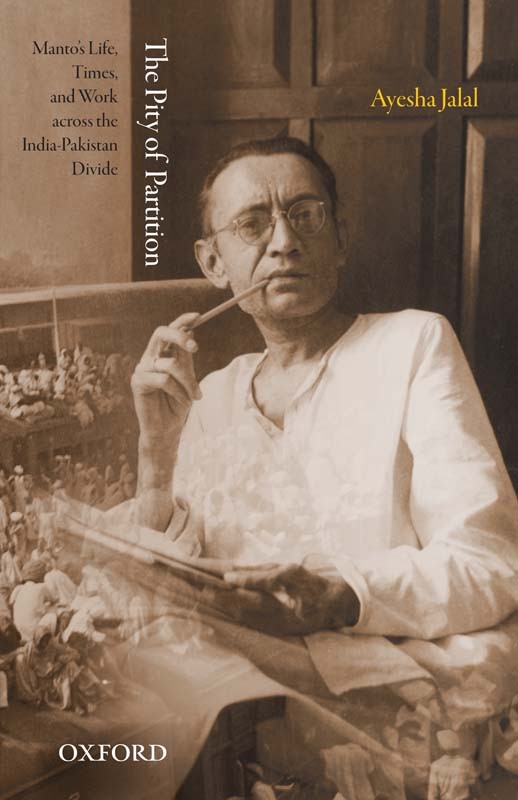

Manto was just 7 years of age when Jalianwala Bagh happened in his native town Amritsar. The tragic incident had left its mark on probably everyone in India at the time but on the minds of the residents of Amritsar the most. While this day epitomized the Indian struggle for independence, the mark it left on the youngsters living in Amritsar at that time was indelible. Bhagat Singh later became the youth’s hero in the colonial India. Just like the other boys of his age, Manto also became a fan of the young martyr. At the age of 19, therefore, Manto, along with his friend Hassan Abbas, was fantasizing himself as a revolutionary who would drive the British out of India. Ayesha Jalal notes in her book ‘The Pity of Partition’, “they spread out a map of the world and plotted their overland escape to Moscow long before any of the subcontinent’s well-known communist intellectuals had come to light”.

This was the time that October Revolution was beginning to inspire the people across the globe for a revolution of the same kind in their home countries. The repression of the colonial era further enhanced the appeal for a revolution in the Asian and African colonies of European imperialists. Manto also started reading Russian literature at this time. He started reading Gorky, Trotsky, Anton Chekhov and Dostoevsky. Quite understandably, his initial writings clearly had a socialist tilt.

Bhagat Singh, Amritsar and ‘Tamasha’

As mentioned earlier, Bhagat Singh and Jalianwala Bagh had played a massive role in Manto’s life. It was Jalianwala Bagh, therefore, which became the topic of his first short story ‘Tamasha’, published in 1934. The story discusses a young boy who was promised by his father that he would take him to a public meeting in the evening. But just before this could happen, General Dyer ordered the infamous massacre of Jalianwala Bagh. Manto, in real life, had been promised by his father the same. It seems that Manto named his own character as Khalid in the short story.

Khalid is told by his father that it wouldn’t be possible for them to go out that day to watch ‘Tamasha’ (the play). Khalid thus starts staring out of the window where a boy catches his eye. The boy is all soaked in blood. Khalid goes to his father and pleads before him to help the kid outside but his father doesn’t. The kid dies outside. Khalid cries bitterly. He asks his mother what was wrong with the boy. The mother tells him that the boy was beaten up by his teacher. Why, he asks. He must have done something wrong, she tells. But he was bleeding, Khalid presses. Mother tells that he must have been hit really hard with the cane. Khalid says the boy’s father must go and scold the teacher then. The teacher is too strong, the mother tells. Is he stronger than the God, he asks. No, not stronger than the God, says mother. Then his father must complain to God for this, Khalid exclaims decisively. Then he turns to God and says he must get the kid the justice or else he’d never talk to God.

This story gives us an insight into the young Manto’s feelings. The way he equates the guns with a cane and the teacher with the British is remarkable. And then he reminds us that the mighty British are not stronger than the God. But at the same time, the rebellious Manto is not happy with mere praying. Even with God, he has his own terms. If the God didn’t listen to him, he wouldn’t talk to Him again.

Inquilab Pasand – A revolutionary

Manto was a true revolutionary. He was not one of those who wanted to just overthrow the government and bring in some new faces. He wanted the real change; change in everything around him. He wanted the society to change. ‘Inquilab Pasand’ that literally translates to ‘Revolutionary’, was another of Manto’s earlier stories. In this story, he plays a young boy whose father has just died and he has fallen all quiet after father s death. When his friend feels worried about him, the boy simply replies, “you know I’m a revolutionary”.

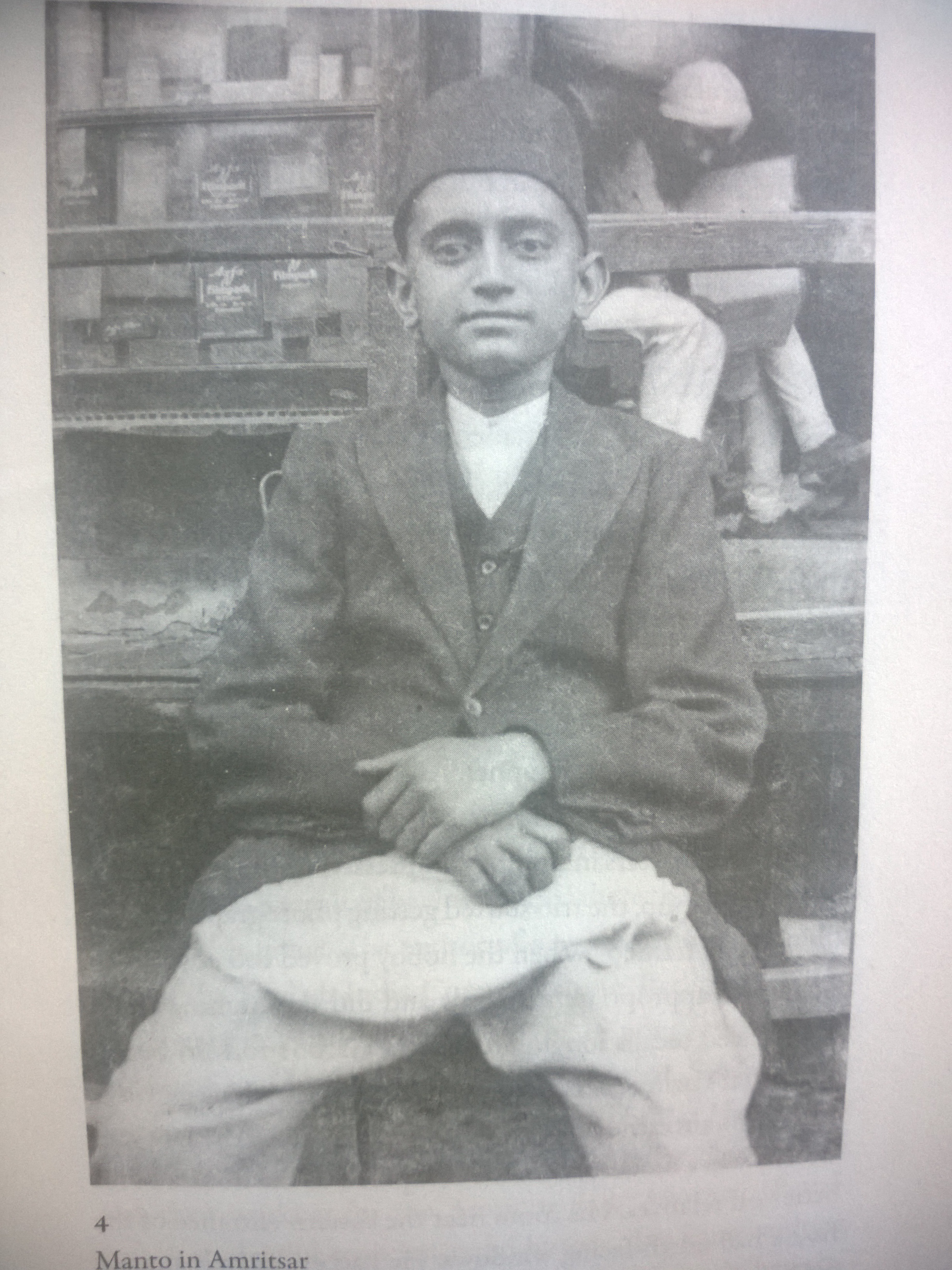

Young Manto in Amritsar

Naya Qanoon (The New Constitution) is yet another such story. Ustad Mangu, a tonga-driver, is the main character. The simpleton runs his tonga near the session court and thus regularly listens to the discussions between the lawyers who board his tonga. He daily listens to their discussions about the new legislation that would bring freedom to the people of India and thus starts fantasizing about a free country. His hopes are only shattered when the new constitution is actually rolled out and he tells a British soldier that he wouldn t let him have a ride on his tonga anymore since the country was free, and the British soldier beats him up.

The story was a satire on India Act 1935, which in Manto’s eyes didn’t change anything in the lives of the common people living in India. Mere legislations and parliamentary reforms didn’t mean anything to him. He wanted something bigger; a change in everything.

Lahore to Bombay

From Amritsar, Manto came to Lahore and started working with his old mentor, and friend, Bari. Though Manto earned 40 rupees a month working for a newspaper named ‘Paras’, he didn’t actually enjoy living in Lahore. Lahore was too backward. His talents could only be polished in a metropolitan like Bombay. In Bombay too, he earned the same amount of money while working for ‘Musawwir’, a film weekly, but the city had too much to offer than just the salary. In Bombay, Manto married Safia. A wife he could always fall back on, Safia was just the right kind of supporter Manto needed. She knew what Manto was and she knew how to live with him. Safia was the only mentor he was left with during the last 15 years of his life, especially after the death of Bibijan in 1940.

Losing Arif and Bibijan

In June 1940, Manto had to face yet another shock in his life when his mother, Bibijan, died. Bibijan had been an inspiration all his life. As discussed earlier, his mother was the only person in the family he could meet since he wasn’t allowed by his brother-in-law to see his sister Balaji. Manto had been married to Safia in 1939 and, as if waiting for getting rid of this responsibility, Bibijan died after just over a year of Manto’s marriage. Although Manto had partially recovered from the trauma of mother’s death when his son Arif was born, he was completely shattered when this son, a short-lived bliss, also died in April 1941. Losing his inspiration and son within a span of just 10 months literally devastated the sensitive writer. However, Manto had to go on.

Kali Shalwar – the first brush with the laws

Manto was charged for obscenity in his novels 5 times in life and was never convicted. ‘Kali Shalwar’ was the first instance when he felt his first brush with the law. The short story, based on the short love affair between two prostitutes (one female and one male), the story was published in the annual number of Adab-i-Latif (Lahore) in 1942. It was banned by the government under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code for obscenity. He was charged for obscenity for 4 more times. Each time, he got away with the conviction due to one reason or the other.

Pakistani actors Nadia Jamil and Faisal Rahman in the drama Kali Shalwaar (2007)

The feminist in Manto

“This society allows a woman to run a brothel, but not a tonga”. These words from “Taangay Wali” are often reverberated while discussing Manto’s advocacy for the women to be allowed to work. But his understanding of the matter was far deeper than generally believed. ‘1919 ki Aik Baat’ is one such story that goes on to narrate his understanding of the misogyny prevalent in our society.

‘1919 ki Aik Baat’ was written in the backdrop of Jalianwala Bagh massacre. ‘Thaila Kanjar’ who was brother of two prostitutes, Shamshad and Almas, takes on the British soldiers who have come to kill the protesters and gets killed in the process, killing one British soldier. His dead body is bemoaned by the entire community. But when his sisters are called by the British soldiers to dance at one of the parties, they entertain them with the dance and at the end, tear their clothes apart. Completely naked, they tell the British soldiers to come and do whatever they want to with the sisters of the young Tufail (Thaila’s real name) who they had martyred. But before that, all they wanted was to spit on their faces. The same community that had mourned Tufail’s martyrdom castigated the sisters “who had disgraced their brother and his martyrdom”.

‘Hatak’ was yet another such story written by Manto. The main character of the story, Saugandhi, who is though a prostitute by profession, yet is so pure at heart that in another world, she might have been a saint. This depiction of the prostitute has remained a recurrent theme in the Urdu and Hindi literature ever since Saugandhi.

This tells how Manto felt about women. He knew that a woman faces misogyny in our society at multiple levels and the attitude that a prostitute has to bear with is the worst form of misogyny. No wonder his funeral was attended by a large number of women wearing Burqas.

Ashk, Krishan Chander and NM Rashid

In 1941, Manto moved to Delhi, the imperial capital, for a job at All India Radio (AIR). This was a critical phase in Manto’s life because this is when he reached new heights of popularity as he wrote about 100 plays at AIR.

He had a much better job now, with a jump of 110 rupees in one go. Manto gave some of his best plays during this period. It was Delhi where he met Krishan Chander, one of the great short-story writers of Urdu and Hindi languages. He stayed at Chander’s apartment and the two worked at the radio together.

Manto made friends, enemies and frenemies at AIR in large numbers. Of all the friends, Krishan Chander was the dearest to him. And Ashk was probably the best frenemy. Ashk didn’t like Manto and Manto didn’t like him either. However, Ashk later claimed in his essay ‘Manto Mera Dushman’ (Manto my enemy) that he never considered Manto an enemy and held him in high esteem.

However, when NM Rashid successfully plotted to transfer Krishan Chander to Lucknow and thus remove Manto’s biggest supporter from the way, it was Ashk who replaced him and made some changes to Manto’s play ‘Awara’. He knew Manto well enough to do it simply out of an urge to make the story better. He knew Manto would never allow a word changed in whatever he wrote. But Ashk still made the changes and Manto stormed out of AIR along with his Urdu typewriter, never to return. Did Ashk really hold Manto in high esteem and never considered him an enemy?

The Pity of Partition

Ayesha Jalal, renowned historian and Manto’s grandniece, titled her book on Manto’s life and times as ‘The Pity of Partition’. Partition literally played a role in Manto’s life that left his soul dismembered. He was born in Amritsar, where his father was a lawyer and wrote extensively on religion. From Amritsar, he moved to Aligarh and then on to Lahore. Bombay was the next station, to which he returned again after his brief stay in Delhi. Manto lived in the pre-partition India and all these cities were like his own to him. He couldn’t understand the concept of dividing a country and carving out two nations out of one, simply on the basis of religion. Aitzaz Ahsan might have taken the pains in trying to prove in his book ‘The Indus Saga’ why it was not a partition based less on religion, and more on geography, language and other ingredients of a nation, Manto wasn’t a sociologist. He was a critic of the society he lived in and the society he lived in was divided on the basis of religion. His masterpiece ‘Mootri’ is a bold and classic depiction of Manto’s thinking about the idea of creating Pakistan, the idea of a United India and his views about Congress and Muslim League. He hated both.

He taunts the frenzy created by the partition riots as if he wasn’t even a part of the community where everything was happening. ‘Kalima Parhiye’ is one such story in which a Muslim kills 3 Hindus out of personal rivalry during the Hindu-Muslim riots and upon being caught swears to God that he killed 3 Hindus but they had nothing to do with Pakistan. It’s a perfect comedy that leaves one guessing whether the common man was actually bothered about the partition or was simply a victim of it.

And then there are stories like ‘Tayaqqun’, ‘Thanda Gosht’ and ‘Khol Do’. These stories literally leave the reader in a state of shock. One would stay paralyzed for several minutes, if not hours, after reading these stories. How a father could rejoice having found a missing daughter who had been raped multiple times, one would think. But what else a father would do if he has no one of acquaintance left on the goddamned planet other than that unfortunate daughter.

Moving to Pakistan

Therefore, Pakistan was never the place Manto wanted to be. As mentioned earlier, he didn’t like Lahore during his first stay here while working for Paras. It has also been discussed earlier that he was never convinced by the idea of partition either. He was a Universalist in true sense of the word. He read Maupassant, Gorky, Victor Hugo, Trotsky, Dostoevsky, Oscar Wilde and anyone from any part of the world. For him, French, English, Russian, Chinese, German, Urdu, all literature was valuable. His disdain for politics of the congress and the Muslim league has already been discussed earlier. He was thus forced by the circumstances to move to Pakistan after the partition. He had no one left in his own family and Safia’s family had already moved to Pakistan. Therefore, they had no other option but to migrate.

When asked which country would he live in after partition, Khushwant Singh had replied, “Wherever goes Lahore”. Manto might have said Bombay, if asked. Khushawant couldn’t live in Lahore. Manto couldn’t live in Bombay. Partition left a lasting impact on Manto’s life. It left a lasting impact on Khushwant’s life too. They were both the ‘Toba Tek Singh’ probably, though a bit crazier than him.

The new country was even more hostile to the one he had been living in so far. Here he was confronted by a more severe kind of censorship and came under heavier criticism for his work then he had ever come while living in the colonial India. The self-professed moral policemen in the country pinched Manto more in the Islamic Republic than they did in the British India.

Manto was booked for ‘Khol Do’ and ‘Thanda Gosht’ in the new country for obscenity. Both were partition stories. ‘Khol Do’ discusses the rape cases involving scouts that were being brushed under the carpet during those days. Manto was told that the story unduly criticized the scouts who had volunteered for the rehabilitation of the refugees.

‘Thanda Gosht’ (Cold Flesh) was the story of a Sikh who went impotent after having kidnapped a Muslim girl who had died of horror by the time he could find a place to rape her.

If Manto could discuss a Sikh in a partition story, he could also take on his ‘fellow Muslim’ scouts. He never took sides. And he never lost hope in humanity. For him, a Sikh could have gone impotent upon looking at a girl who had died of horror though he was going to rape her anyways and a father could rejoice finding back his daughter though she had been raped so many times that she would simply untie her belt upon hearing the words ‘Khol Do’ (open). Manto certainly had the guts to challenge what was believed.

Letters to Uncle Sam, Manto’s political side

Although he didn’t like discussing politics, he wasn’t a political illiterate. He certainly read newspapers and magazines. It’s just that he looked at things in a different way. He didn’t want to read the statements by Jinnah or Gandhi in the headlines of the newspapers. His sensitive side never allowed him to give the attention to those statements. For him, the blood that was being spilt on both sides of the borders was the only headline.

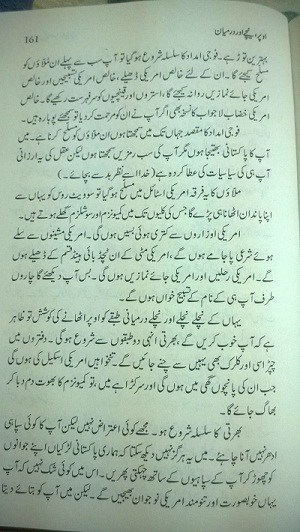

An excerpt from a Letter to Uncle Sam

But his political maturity can be gauged by the series of letters he wrote to Uncle Sam (read United State) calling him his uncle and playing his nephew. Manto died in 1955, long before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. By that time, there were no Taliban, no al-Qaeda, no IS and no Osama bin Laden. Pakistan had not even signed the SEATO and CENTO agreements by that time. It was then when Manto said that all the US wanted out of Pakistan was its Mullahs. He said that the US will use these Mullahs for its own gain and make them fight the Soviets instead of taking the Red Elephant on by itself. He wrote at that time that the US would arm these Mullahs and wanted to create a theocratic state out of Pakistan because only that kind of Pakistan would help the neo-imperialist US to further its agenda against the communist Russia. The events that unfolded a couple of decades later proved precisely this.

786

Was he religious or not cannot really be determined. Manto did not observe the five prayers a day, nor is he ever found indulging into religious rhetoric. However, when he begins writing a piece, he inscribes the numbers ‘786’ just above the title. It is said that his mother had advised him to do so, Manto, though rarely, also displays humility at times. It is such times only when he resorts to the idea of God. As he writes in ‘Mein Kyun Likhta Hoon’, Manto says, “Saadat Hasan Manto writes because he is not as great a storyteller and poet as God. It is his lowliness that makes him write”.

Apart from these rare outbursts, Manto was hardly a religious man, often lingering on the sidelines of blasphemy as well. For example, in a film story, he titled as ‘Parosi’, Manto describes the intercommunal tensions between the Hindus and Muslims in Bombay during the turmoil years just before the Partition. Since he believed that the mosque and the temple could never come closer and would never allow the members of the two communities to meet inside any of them, he made them meet at the home of a prostitute.

Although most would issue the sermon that Manto had committed blasphemy here, he was actually highlighting the fact that religion also had the tendency to create divide. To him, religion was a personal thing. Insignias, symbols, building structures could not define religion according to him.

Manto Lives on

It’s been 61 years since he died. Manto has been translated into dozens of foreign and local languages and his prose continues to inspire hundreds of thousands even today. In 2015, Sarmad Sultan Khoosat directed the movie based on Manto’s life in Lahore after the partition. Sarmad played Manto in the movie and his acting was phenomenal. He recently won the Best Actor award at Jaipur International Film Festival (JIFF) 2016 in India for the movie. He has played a critical role in introducing the youth of the country to one of the greatest short-story writers of all times and of all languages. The movie was low-budget and did fairly well on the Box Office but the impact it created was massive. It reopened Manto’s chapter to discussion.

.jpg)

Manto hated stereotypes. This is why he named his son as ‘Yazeed’ in his story ‘Yazeed’ because he believes that there’s nothing in the name. If that Yazeed had held the people from drinking water, another one could free the waters from the oppresser.

He was always ready to give a second chance. He always believed that a human is first and last a human and this is the quality a human can never lose. The basic humanness of a human lives on. This is why Eeshar Singh becomes impotent upon discovering that the girl in his hands had turned into ‘Thanda Gosht’.

Today, when Pakistan, and the world at large, is faced with extremism and its more violent forms, Manto certainly is the ideology that counterbalances this fanaticism prevalent in the society. Today, more than ever, we need to read Manto. “And it is also possible, that Saadat Hasan dies, but Manto remains alive”, he once said. Today, is his 61st death anniversary, but... Manto lives on!

The story has been written by Ali Zaidi. It frequently refers to Ayesha Jalal’s book The Pity of Partition and the images of Manto and his parents in the story have also been taken from the same book.