Bringing Private King home: reaching Pyongyang is the first challenge

World

King, an active-duty U.S. Army soldier serving in South Korea, had sprinted into North Korea

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - It has never been easy for the United States to secure the return of citizens from North Korea, one of the world's most isolated nations.

The task may be even harder in the case of Private Travis King, with communication between the countries now almost non-existent, say diplomats and negotiators.

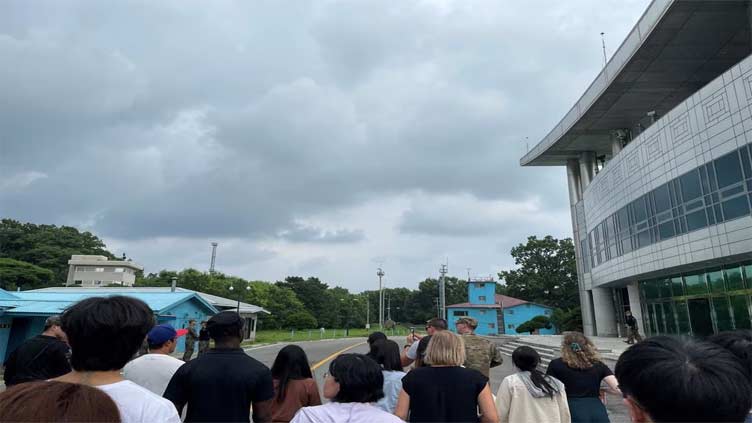

King, an active-duty U.S. Army soldier serving in South Korea, sprinted into North Korea while on a civilian tour of the Demilitarized Zone on the border between the two Koreas.

Washington is fully mobilized in trying to contact Pyongyang about him, U.S. Army Secretary Christine Wormuth said on Thursday, but North Korea had yet to respond.

Since U.S. President Joe Biden took office in 2021 the limited contacts between Washington and Pyongyang have all but ceased as the Trump administration's efforts to negotiate over North Korea's nuclear weapons program fizzled and North Korea sealed its borders in response to COVID-19.

It's a different situation than what most earlier negotiators faced.

"The North Koreans have shown no interest in dialogue with us at this point," said Thomas Hubbard, a retired U.S. ambassador who traveled to Pyongyang in 1994 to bring back Bobby Hall, the last serving member of the U.S. military held in North Korea.

At that time, U.S. officials had just concluded an initial nuclear agreement with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un's father, Kim Jong Il.

"We were in a very different time," said Hubbard. "The North Koreans saw they had some stake in the relationship with the United States."

LIMITED OPTIONS

U.S. negotiators have few ways of reaching the North Koreans. The countries have no diplomatic relations and Sweden, which officially represents U.S. interests in Pyongyang, pulled out its diplomats in August 2020 amid the coronavirus pandemic.

U.S. officials said the United States had attempted to reach North Korea about King through the United Nations Command hotline and other channels, including the U.N. in New York, where North Korea has a representative.

The best approach for now, said experts, may be a low-key public stance.

"About 90% of (the outcome) will be determined based on how we react right now," said Mickey Bergman, executive director of the Richardson Center set up by Bill Richardson, a former diplomat who has previously negotiated with North Korea for the release of detainees.

North Korea would likely interrogate King at length, then have an option of deporting him or charging him, said Bergman, adding that the U.S. should avoid "pounding our chest" and instead calmly communicate that Washington respects Pyongyang's right to detain and question a soldier who entered its territory.

Jenny Town, of Washington's 38 North think tank, said the case was complicated by not knowing King's intentions and whether he actually wanted to return. King had been detained in South Korea for more than a month for assault and was to fly back to the U.S. to face military discipline.

Cases of U.S. soldiers going to North Korea are extremely rare. In 1965, Charles Robert Jenkins, a 25-year-old U.S. Army sergeant walked over DMZ and spent four decades in North Korea, where he taught English and also portrayed a U.S. spy in a propaganda film.

‘HE’S NOW THEIR PAWN’

A former North Korean diplomat who defected to South Korea said King may be used as a propaganda tool, but it was not clear how long North Korea would want to exploit his presence.

"Holding an American soldier is probably a not very cost-effective headache for the North in the long run," said Tae Yong-ho, now a member of South Korea's parliament.

A cautionary case of North Korean detention is that of Otto Warmbier, a college student detained on a tour in 2015 and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for trying to steal an item with a propaganda slogan.

Warmbier was eventually returned to the United States in a coma in 2017, but died days later.

Otto’s father Fred feels empathy for King and his family.

"This is about a young man – we don't know his mental condition," he told Reuters in an interview. "He’s now their pawn. If it was any other country in the world, there would be communication now."

When asked about King, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Friday said the Biden administration had repeatedly tried to re-establish dialogue with Pyongyang since taking office, offering new nuclear talks without preconditions.

"We sent that message several times," Blinken told the Aspen Security Forum. "Here's the response we got: one missile launch after another," referring to repeated North Korean missile tests.