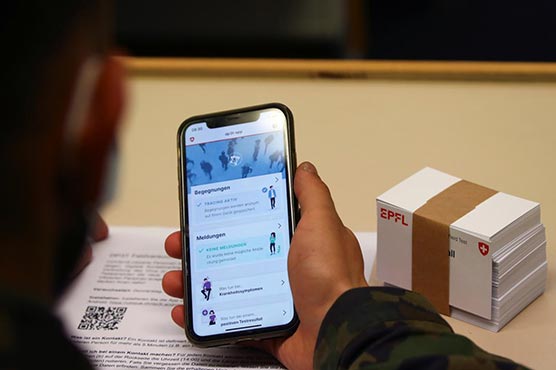

Swiss soldiers pick up smartphones to fight COVID-19

Switzerland hopes to launch the app on May 11.

CHAMBLON, Switzerland (Reuters) - In the battle against coronavirus, Swiss soldiers are using smartphones to test a new contact tracing application that could prevent infections while also protecting users’ privacy.

Switzerland hopes to launch the app on May 11 based on a standard, developed by researchers in Lausanne and Zurich, that uses Bluetooth communication between devices to assess the risk of catching COVID-19.

A hundred soldiers from the Chamblon army base near Lausanne volunteered to download the app and then go about their regular routines for 24 hours.

If they spend 15 minutes within two metres of each other, that information is logged on their devices and they must exchange a validation card given by researchers so the data can be checked.

The apps “do that in an encrypted way, and the records stay on the phone”, Marcel Salathe, director of the digital epidemiology lab at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), told Reuters Television.

“If a person eventually gets positively tested, they can upload their ID to the system and then all the other apps can check whether they have been close to that person and can then call the health authorities,” he added.

Speed is vital. COVID-19 can be spread by people without symptoms, making it important to react quickly when an individual tests positive and warn those they have contacted.

“The idea of this app is really to aid contact tracing,” said Salathe. “Usually this is done in a way that is person based, and with this app, we hope to support this process so that it is much faster.”

LIKE A SUBMARINE

EPFL project manager Alfredo Sanchez compared the app to “a submarine that sends sound markers and listens to the echoes that are coming back”.

Although early results with Bluetooth-based contact tracing in countries like Singapore have been modest, backers say it can help if large numbers participate.

Amid concerns about whether such technology can be used by governments to increase surveillance, the Swiss team has taken a privacy-first approach.

Records of Bluetooth exchanges between smartphones are kept on devices, not on a central server.

Salathe warned that, with a central server, “you start adding more and more things that, on their own, don’t look very problematic. But, actually, you are slowly building something that is very close to a really intrusive surveillance machinery.”

The Swiss app would be the first of its kind to have a decentralized design compatible with new standards from Apple and Google, whose operating systems run 99% of the world’s smartphones.

In Geneva, people’s views on the app are mixed.

Hamza Fawaz, a resident in his 30s, has doubts about data protection and will not use the app. But conference interpreter Beatrice Mallet, in her 60s, is “completely ready”.

“It can be useful and if it allows us to get out more quickly from this health crisis, this is a good thing”, she said.

The Swiss Parliament is expected to debate the app next week.