Sailing among the stars: how photons could revolutionise space flight

It's been the stuff of scientists' dreams for decades but has only very recently become a reality.

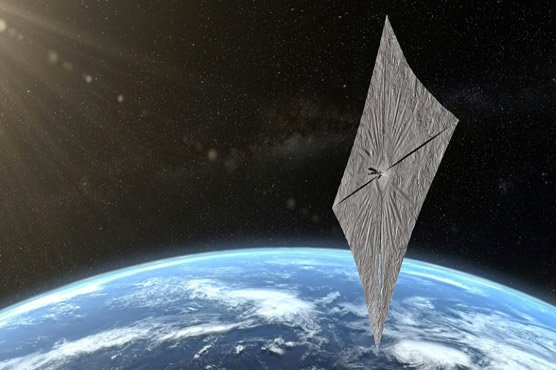

WASHINGTON (AFP) - A few days from now, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket will lift off from Florida, carrying a satellite the size of a loaf of bread with nothing to power it but a huge polyester "solar sail."

It’s been the stuff of scientists’ dreams for decades but has only very recently become a reality.

The idea might sounds crazy: propelling a craft through the vacuum of space with no engine, no fuel, and no solar panels, but instead harnessing the momentum of packets of light energy known as photons -- in this case from our Sun.

The spacecraft to be launched on Monday, called LightSail 2, was developed by the Planetary Society, a US organization that promotes space exploration which was co-founded by the legendary astronomer Carl Sagan in 1980.

But the idea itself has been around for a lot longer than that.

"In the 1600s, Johannes Kepler talked about sailing among the stars," Bill Nye, the chief executive of the Planetary Society, told AFP.

Kepler theorized that sails and ships "could be adapted to the heavenly breezes," and "it turns out, there really is. It’s not just poetry," said Nye, who is known in the US as the "Science Guy" after the children’s TV show which brought him national fame in the 1990s and who now hosts a Netflix program.

And building a solar sail doesn’t require cutting-edge tech as you might imagine.

It’s essentially a large square of very thin film (less than the width of a human hair), which is also ultra-light and reflective.

It has an area of 32 square meters and is made from Mylar, a brand of polyester that has been on the market since the 1950s.

As photons bounce off the sail, they transfer their momentum in the opposite direction to the bouncing light.

"The bigger and shinier and lower mass the spacecraft, the more of a push it gets," explains Nye.

The thrust provided by these photons is tiny -- but it’s also unlimited. "Once you’re in orbit, you never run out of fuel," he said.

Japan’s space agency launched a solar sail in 2010, dubbed Ikaros, but others haven’t been able to fully test the concept.

"It’s a romantic idea whose time has finally come," said Nye. "We hope this technology catches on."

Unlimited energy

Its predecessor was LightSail 1, launched in 2015. But its mission, which lasted a few days, experienced problems and was intended only to test deployment of the sail.

LightSail 2 cost $7 million, a relative pittance in space mission terms. It is envisaged to remain in orbit for a year, and represents a more definitive proof of concept.

"We want to democratize space exploration," enthused Nye, who has invited universities and businesses to take up the technology.

A few days after its launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, LightSail 2 will open its hinged solar arrays, then deploy the four triangular parts of its sail, which together form a giant square.

For this demonstration, solar panels will provide power for the satellite’s other functions such as photography and ground communications.

As it orbits the Earth, it will begin to increase its altitude thanks to the pressure of solar radiation on the sail.

So what do we see the technology being used for in the near future?

For a start, it could facilitate deep space exploration. Though it starts off much slower than a spaceship powered by fuel, it will continue to accelerate permanently through space, eventually achieving breathtaking speeds.

The other application would be in maintaining a probe at a stationary point in space, which would require corrections to be made infinitely. For example, a telescope that looks out for asteroids in the vicinity of Earth, or a satellite that needs to be fixed in a stationary orbit above the North Pole.

"You’d need an enormous amount of rocket fuel to keep stationary for 10 years. It’s just not practical," said Nye.

Photons, on the other hand, are unlimited.

As a bonus, said the scientist, "You’ll be able to see it from the ground," with the naked eye.