Movie Review: Documentary 'The Eternal Memory' shows that love is stronger than dementia

Entertainment

The documentary is the story of one man’s decline due to Alzheimer’s disease

(AP) - “The Eternal Memory” begins with a confused Augusto Góngora waking up one morning as his wife of two decades gently greets him.

“Nice to meet you,” he tells her.

The loving, lyrical Maite Alberdi -directed documentary is the story of one man’s decline due to Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s so much more. It’s a stronger love story and one that tries to say things about a country’s collective memory, too.

Góngora, a journalist, author and TV host, documented the crimes in his native Chile by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. He and his wife, actress and academic Paulina Urrutia, are the stars of “The Eternal Memory,” which documents his growing disorientation and unmooring.

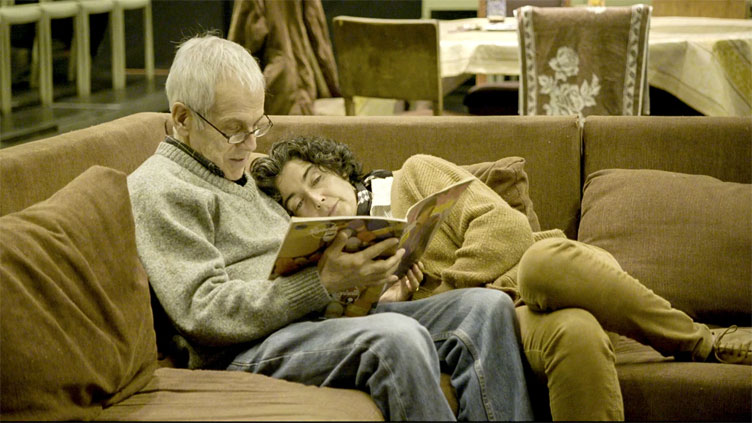

It is a very intimate work, navigating the lost spaces in a ravaged mind, the camera going into their bedroom and even a shower stall. We watch Urrutia shave her husband, dry him with a towel like a child and read to him as they take a walk.

“I’m someone that has come here to help you remember who Augusto Góngora was,” she tells him.

Alberdi assembled some 40 hours of footage, augmented by 20 more that Urrutia captured when the couple was alone. The director also switches back in time to capture Góngora as a vibrant TV reporter and in home movies as a doting dad, his white hair turning black and a mustache suddenly sprouting on the younger man.

It is hard to watch the vibrant, articulate man in those old images struggling in his last years. He gets confused by his reflection in a glass door — “We know each other,” he tells his wife. Later, he sobs in frustration: “Something very strange is happening here. Help me, please.”

Throughout is Urrutia, the very definition of a loving spouse, patient and trying not to take it personally that her husband is drifting away and not always knowing who she is.

“My love, you’re never alone. Never. Never,” she tells him.

Urrutia brings her husband to rehearsals for her play — they hold hands while going over her lines — exercise together, watch an eclipse, spontaneously dance in a gym and rewatch their marriage video. She is always trying to pull out memories, sharpen his mind, sooth his outbursts.

The third prong of this film — following the dementia and the love story — is the memory of Chile. This is perhaps the weakest link in Alberdi’s movie, but the one most intriguing. The director tries to connect Góngora’s evaporating memory to that of his nation’s collective forgetting of its 1970s Pinochet trauma. It’s a large leap and not always neatly done, but an admirable attempt.

What is more devastating is Góngora’s own warning about memory loss. In a handwritten inscription to his wife in one of his books he writes: “Without memory, we wander confused, not knowing where to go.”

The couple share tears and laughter as he tries to remember what they ate on their first date and if he had any children already. “Since we met, you’ve given me so many wonderful things,” he tells her.

Later, he will cry over the thought of losing his treasured books. “What if somebody takes my books?” he cries out. “What is happening to me?”

The film won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival this past January. Góngora died on May 19 at age 71. But he bravely left behind a moving document about how to live a meaningful life and how to fight for dignity even as the mind crumbles. And, most importantly, he taught us how to love and be loved.