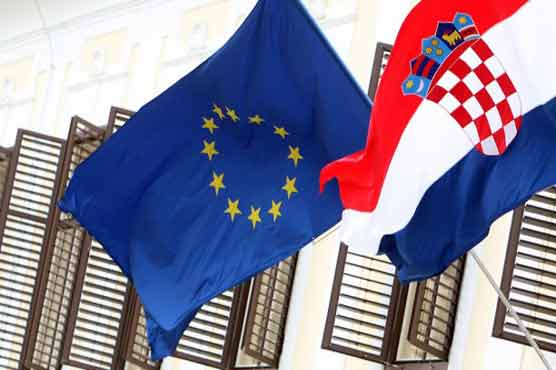

Croatia ready to enter European Union

Croatia is the first new member in six years and the second only from the former Yugoslavia.

LJUBLJANA (AFP) - "You ll be joining us in hell soon!" Slovenians like to joke as neighbouring Croatia prepares to enter the European Union, the first new member in six years and the second only from the former Yugoslavia.

In truth, most of the 10 eastern European countries that joined the bloc in 2004 and 2007 are overwhelmingly positive about a union that has brought them infrastructure money, a higher standard of living, more freedom of movement and an escape from Russia s sphere of influence.

Compared to the older EU members, the newcomers -- from Estonia in the north to Bulgaria in the south -- consistently top Eurobarometer surveys looking at public opinion of the EU.

Infrastructure in countries that once stood behind the Iron Curtain has been radically improved in many places, thanks to EU funds.

"For the first time, there s a rubbish collecting service in my grandmother s village," Cristian Ghinea, a Romanian political anayst, told AFP.

Poland, the largest recipient of structural and cohesion funds with an allocated 67.3 billion euros ($88.65 billion) in 2007-2013, has built or renewed over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 miles) of roads and 1,600 kilometres of railways.

Next door in Hungary, the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban -- usually so critical of Brussels -- has worked hard to bring its deficit in line for fear of losing EU funds that are crucial to its construction sector.

Judiciary reforms and continued pressure by Brussels, even after entry into the bloc, have meanwhile helped bring top politicians and businessmen to justice in corruption-plagued countries like Bulgaria and Romania.

As a result, trust in European institutions is sometimes higher than in the national government.

"EU entry has been a very good thing as it forced politicians to carry out reforms," said Atena, a Bucharest bank employee.

"What EU membership did for all those countries was this tremendous transition process, it was unprecedented," Anton Rop, the prime minister who took Slovenia into the bloc, told AFP.

"Slovenia had to change substantially... it moved towards the living standards of the most developed countries in the EU."

Another cherished benefit has been the ability to move freely across EU borders.

Two million Poles and as many Romanians currently work and live abroad, sending billions of euros back home. Lithuanians have also left in droves and up to 500,000 Hungarians have departed since 2010.

In Bulgaria, over 70 percent of families encourage their children to study abroad, with 36 percent pushing them to leave definitely, according to the NCIOM institute.

-- Too many imports --

On a summer s day in Ljubljana, the bells of St. Nicholas Cathedral cheerfully play Beethoven s "Ode to Joy" -- the EU s anthem -- as the clock strikes noon.

Around the city, ministries, courthouses and other official buildings proudly fly the EU s blue flag with the ring of stars.

For small countries long dominated by the Soviet Union, EU membership has meant recognition as democratic states, a bigger role in international affairs and escape from Moscow.

"Lithuania is much safer now," noted Petras Austrevicius, an MP who helped negociate Lithuania s accession to the EU.

But the picture is not all rosy and at Ljubljana s central market, amid mounds of leafy salads, luscious apricots and mouth-watering cherries, vendors complain of the EU s impact on the economy and their own pockets.

"There are too many imports. People have stopped trusting vendors, they always ask if the vegetables are really local," Marinka, a 64-year-old woman selling courgettes and potatoes, says without losing her smile.

"We were ok before joining, we didn t have to join."

Tanja, 26, a tourism student, says it s hard to get a job and she is considering moving to neighbouring Austria.

"Prices went up 100 percent or more but paychecks stayed the same. Coffee used to be 50 cents now it s 1.30 euro," she says.

While the EU has facilitated trade and investments to some extent, foreign competition and strict regulations caused the closure of thousands of Bulgarian food companies that failed to respect EU standards.

Bulgaria and Romania -- the most recent newcomers in 2007 -- remain the bloc s poorest members and in Hungary and the Czech Republic, eurosceptic rhetoric from the government is common, dampening enthusiasm also among the population.

Grumblings are meanwhile heard from Prague to Bucharest that the eastern newcomers have too little weight in Brussels, compared to Berlin or Paris.

"Poland (is) one of the five or six countries without which no decision can be taken in the EU," Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski insisted recently to the daily Gazeta Wyborcza.

The newcomers say their location and history give them an advantage in dealings with Russia and prospective EU candidates in the Balkans.

With the global economic crisis causing higher unemployment and austerity, and given the high hopes before entry, some disillusionment has been inevitable.

But more benefits could yet come from the EU, for instance through better use of its funds, a large proportion of which is never used.

"We cannot say that we have managed to make the best use of all the political, economy and security benefits stemming from our membership," Romanian President Traian Basescu admitted earlier this year.