Breakthroughs in race to create lab models of human embryos raise hopes and concerns

Technology

Most accurate models developed so far

(Web Desk) - It’s still one of the biggest mysteries in science: How does a human cell — too small to see with the naked eye — divide and reproduce to ultimately become a human body made up of more than 30 trillion cells?

From the moment sperm fuses with an egg, human embryo development involves a string of complex and little understood processes.

Much of what is known about embryo development comes from animals such as mice, rabbits, chickens and frogs, with research on human embryos very tightly controlled and regulated in most countries.

But animal studies can only tell researchers so much. What happens during human embryo development, particularly in the crucial first month, remains largely unknown.

“The drama is in the first month, the remaining eight months of pregnancy are mainly lots of growth,” said Jacob Hanna, a professor of stem cell biology and embryology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

“But that first month is still largely a black box.”

Being able to peer into that black box would open up a world of biomedical possibilities, allowing scientists to demystify a previously obscure window of embryo development — ultimately leading to a better understanding of miscarriages, congenital birth defects and the side effects of medications taken during pregnancy.

And some researchers believe they’ve found a way to do it that bypasses the need for eggs or sperm.

Harnessing advances in stem cells, labs around the world are making embryo-like structures — a group of cells that acts like an embryo but can’t grow into a fetus.

Recent breakthroughs in the field, the culmination of years of painstaking lab work, have generated hope and some alarm, raising urgent questions about the ethical status of these models, to what extent they should be treated like human embryos and whether they are open to misuse.

What exactly have scientists achieved?

The embryo-like structures are essentially clumps of cells grown in a lab, which are smaller than a grain of rice and represent the very earliest stages of human development, before any organs have formed.

They don’t have a beating heart or a brain.

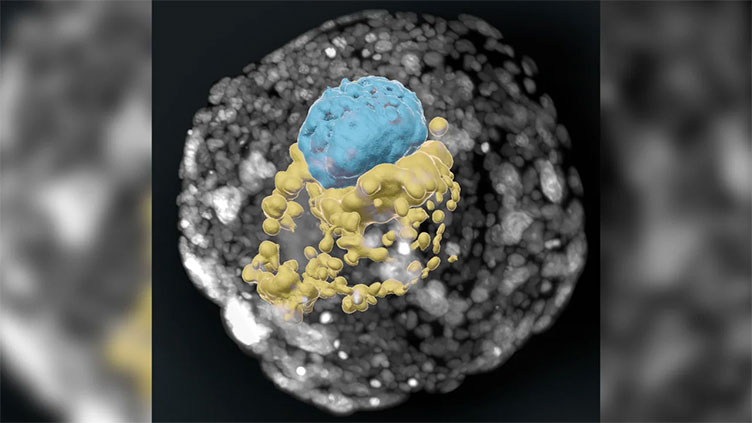

The most advanced models, revealed in September by an Israeli team that Hanna was part of, show all the cell types that are essential for an embryo’s development — the placenta, yolk sac, chorionic sac (outer membrane) and other tissues that an embryo needs to develop.

The structures were left to develop for eight days — reaching a developmental stage equivalent to day 14 of a human embryo in the womb — an important moment when natural embryos acquire the internal structures that enable them to proceed to the next stage: developing the progenitors of body organs.

Hanna said they were the most accurate models developed so far and, unlike those created by other teams, no genetic modification had been made to turn on the genes necessary to generate the different types of cells, only chemical nudges.

“It’s not only you put the cells together, and they’re there,” he said. “But you see the architecture, you start also seeing very fine details,” Hanna said.