Ultrasound device may help deliver chemotherapy drugs to treat brain cancer

These ultrasound devices are designed to create a large opening in the barrier

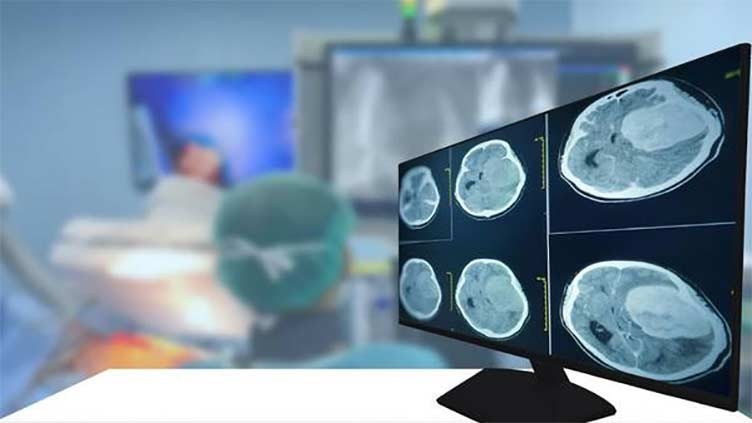

ISLAMABAD, (Online) - New research has opened a possible doorway for treating glioblastoma, the deadliest form of brain cancer.

Brain tumors are especially difficult to treat. Part of the reason is that most chemotherapy drugs are blocked by the blood-brain barrier, which controls what can pass from the bloodstream to the brain.

To get around the problem, researchers from Northwestern Medicine used an ultrasound device implanted in the brain to temporarily open the blood-brain barrier, allowing chemotherapy drugs to be delivered to the brain via intravenous injection.

“Finding that a new technology can safely and effectively open the blood-brain barrier to deliver chemotherapy is a potentially game-changing step forward in brain cancer research and treatment,” Dr. Jason Salsamendi, the lead interventional radiologist at the City of Hope Orange County Lennar Foundation Cancer Center in California, told Medical News Today.

The 4-minute procedure, which takes place while patients are awake, was repeated every few weeks over a 4-month period, for a total of six sessions.

The study, published in the journal Lancet Oncology, reports that the procedure resulted in nearly a four-fold to six-fold increase in the concentration of chemotherapy drugs in the brain.

The importance of new brain cancer treatment

“This is potentially a huge advance for glioblastoma patients,” said Dr. Adam Sonabend, a study lead investigator and a neurosurgeon and associate professor of neurological surgery at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Illinois. “While we have focused on brain cancer… this opens the door to investigate novel drug-based treatments for millions of patients who suffer from various brain diseases.”

“Systemic delivery through IV is common and easy to perform,” Dr. Albert Kim, director of the Brain Tumor Center at Washington University in St. Louis’s Siteman Cancer Center who was not involved in this study, told Medical News Today.

Nonetheless, Kim noted that while ultrasound has been used in the past to open the blood-brain barrier, “the implantable device allows for repeated openings, which could enable delivery of multiple cycles of systemic drugs.”

The study involved paclitaxel and carboplatin, two potent chemotherapy drugs that normally cannot be used to treat glioblastoma.

The main chemotherapy drug currently used to attack glioblastoma, temozolomide, can pass through the blood-brain barrier, but it is comparatively weak.

Past studies showed that injecting paclitaxel directly into the brain can be effective, but carries the risk of brain irritation and meningitis.

“Glioblastoma currently has a five-year survival rate of only around 10 percent and patients have not benefitted from advances, such as targeted agents and immunotherapy, that have been made in recent years to treat other cancers,” said Salsamendi. “Being able to deliver chemotherapy across the blood-brain barrier would be an alternative to delivering treatment directly into the brain each time a dose needs to be given.”

Opening the blood-brain barrier

The researchers in the new study reported that the blood-brain barrier closed rapidly after being forced open — typically within 30 to 60 minutes.

“The longer the blood-brain barrier remains open, the greater the potential risk that something harmful could make its way into the brain,” noted Salsamendi. “Knowing as precisely as possible the length of time the barrier may be open would be a key consideration in treatment planning and risk reduction.”

The ultrasound device, which uses a stream of microbubbles to open the blood-brain barrier, was developed by the French biotech company Carthera.

These ultrasound devices are designed to create a large opening in the barrier, crucial to increase the efficacy of chemotherapy delivered to a larger region of the brain after tumors are surgically removed.

The same group of researchers is now conducting clinical trials to determine whether delivering paclitaxel and carboplatin across the blood-brain barrier prolongs survival among people with recurring glioblastoma tumors. The two drugs, used in combination, have proven effective in treating other types of cancer.