Biden's chip dreams face reality check of supply chain complexity

Biden's chip dreams face reality check of supply chain complexity

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - To understand President Joe Biden’s challenge in taming a semiconductor shortage bedeviling automakers and other industries, consider a chip supplied by a U.S. firm for Hyundai Motor Co’s new electric vehicle, the IONIQ 5.

Production of the chip, a camera image sensor designed by On Semiconductor, begins at a factory in Italy, where raw silicon wafers are imprinted with complex circuitry.

The wafers are then sent first to Taiwan for packaging and testing, then to Singapore for storage, then on to China for assembly into a camera unit, and finally to a Hyundai component supplier in Korea before reaching Hyundai’s auto factories.

A shortage of that image sensor has led to the idling of Hyundai Motor’s plant in South Korea, making it the latest automaker to suffer from global supply woes that crippled production at most automakers including General Motors Co and Ford Motors Co and Volkswagen.

And the winding journey of the image sensor shows just how complicated it will be for the chip industry to both ramp up capacity to address the current shortage and re-invigorate U.S. chip manufacturing.

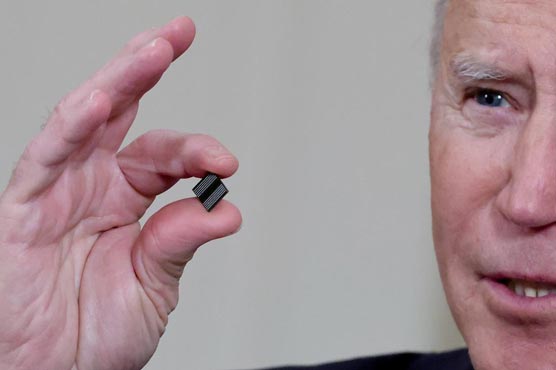

U.S. President Joe Biden on Monday convened semiconductor industry executives in Washington to discuss solutions to the chip crisis, the latest move in a broader effort to bolster the domestic chip industry. He’s also proposed $50 billion to support chip manufacturing and research as part of his $2 trillion infrastructure proposal, which he said would help the United States win the global competition with China.

Much of that money will likely go towards the construction of multi-billion-dollar advanced chip plants by Intel, Samsung and TSMC. But industry executives say addressing the broader supply chain is crucial, and the Biden administration faces complicated choices on which elements of it to subsidize.

“Trying to reconstruct an entire supply chain from upstream to downstream in a single given location just isn’t a possibility,” David Somo, senior vice president at ON Semiconductor, told Reuters. “It would be prohibitively expensive.”

The United States now only accounts for about 12% of worldwide semiconductor manufacturing capacity, down from 37% in 1990. More than 80% of global chip production now happens in Asia, according to industry data.