Scientists develop device to generates electricity 'out of thin air'

"We are literally making electricity out of thin air," says electrical engineer Jun Yao.

They found it buried in the muddy shores of the Potomac River more than three decades ago: a strange "sediment organism" that could do things nobody had ever seen before in bacteria.

This unusual microbe, belonging to the Geobacter genus, was first noted for its ability to produce magnetite in the absence of oxygen, but with time scientists found it could make other things too, like bacterial nanowires that conduct electricity.

For years, researchers have been trying to figure out ways to usefully exploit that natural gift, and they might have just hit pay-dirt with a device they’re calling the Air-gen. According to the team, their device can create electricity out of… well, almost nothing.

"We are literally making electricity out of thin air," says electrical engineer Jun Yao from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. "The Air-gen generates clean energy 24/7."

The claim may sound like an overstatement, but a new study by Yao and his team describes how the air-powered generator can indeed create electricity with nothing but the presence of air around it. It’s all thanks to the electrically conductive protein nanowires produced by Geobacter (G. sulfurreducens, in this instance).

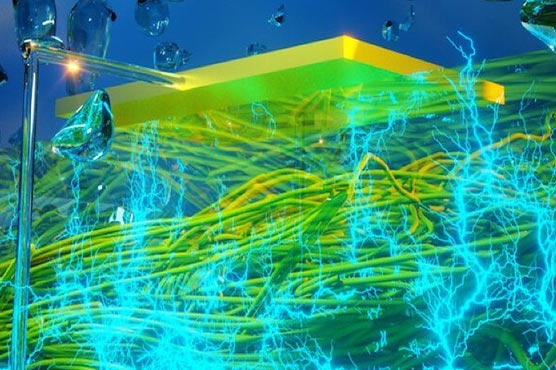

The Air-gen consists of a thin film of the protein nanowires measuring just 7 micrometres thick, positioned between two electrodes, but also exposed to the air.

Because of that exposure, the nanowire film is able to adsorb water vapour that exists in the atmosphere, enabling the device to generate a continuous electrical current conducted between the two electrodes.

The team says the charge is likely created by a moisture gradient that creates a diffusion of protons in the nanowire material.

"This charge diffusion is expected to induce a counterbalancing electrical field or potential analogous to the resting membrane potential in biological systems," the authors explain in their study.

"A maintained moisture gradient, which is fundamentally different to anything seen in previous systems, explains the continuous voltage output from our nanowire device."

The discovery was made almost by accident, when Yao noticed devices he was experimenting with were conducting electricity seemingly all by themselves.

"I saw that when the nanowires were contacted with electrodes in a specific way the devices generated a current," Yao says.

"I found that exposure to atmospheric humidity was essential and that protein nanowires adsorbed water, producing a voltage gradient across the device."

Previous research has demonstrated hydrovoltaic power generation using other kinds of nanomaterials – such as graphene – but those attempts have largely produced only short bursts of electricity, lasting perhaps only seconds.

By contrast, the Air-gen produces a sustained voltage of around 0.5 volts, with a current density of about 17 microamperes per square centimetre. That’s not much energy, but the team says that connecting multiple devices could generate enough power to charge small devices like smartphones and other personal electronics – all with no waste, and using nothing but ambient humidity (even in regions as dry as the Sahara Desert).

"The ultimate goal is to make large-scale systems," Yao says, explaining that future efforts could use the technology to power homes via nanowire incorporated into wall paint.

"Once we get to an industrial scale for wire production, I fully expect that we can make large systems that will make a major contribution to sustainable energy production."

If there is a hold-up to realising this seemingly incredible potential, it’s the limited amount of nanowire G. sulfurreducens produces.

Related research by one of the team – microbiologist Derek Lovley, who first identified Geobacter microbes back in the 1980s – could have a fix for that: genetically engineering other bugs, like E. coli, to perform the same trick in massive supplies.

"We turned E. coli into a protein nanowire factory," Lovley says.

"With this new scalable process, protein nanowire supply will no longer be a bottleneck to developing these applications."

The findings are reported in Nature.