Iceland commemorates first glacier lost to climate change

Glaciologists stripped Okjokull of its glacier status in 2014, a first for Iceland.

REYKJAVIK (AFP) - Iceland on Sunday honoured the passing of Okjokull, its first glacier lost to climate change, as scientists warn that some 400 others on the subarctic island risk the same fate.

As the world recently marked the warmest July ever on record, a bronze plaque was mounted on a bare rock in a ceremony on the former glacier in western Iceland, attended by local researchers and their peers at Rice University in the United States who initiated the project.

Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir and former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson also attended the event, as well as hundreds of scientists, journalists and members of the public who trekked to the site.

"I hope this ceremony will be an inspiration not only to us here in Iceland but also for the rest of the world, because what we are seeing here is just one face of the climate crisis," Jakobsdottir told AFP.

The plaque bears the inscription "A letter to the future", and is intended to raise awareness about the decline of glaciers and the effects of climate change.

"In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it," the plaque reads.

It is also labelled "415 ppm CO2", referring to the record level of carbon dioxide measured in the atmosphere last May.

The plaque is "the first monument to a glacier lost to climate change anywhere in the world", Cymene Howe, associate professor of anthropology at Rice University, said in July.

"Memorials everywhere stand for either human accomplishments, like the deeds of historic figures, or the losses and deaths we recognise as important," she said.

"By memorialising a fallen glacier, we want to emphasise what is being lost -- or dying -- the world over, and also draw attention to the fact that this is something that humans have ‘accomplished’, although it is not something we should be proud of."

Howe noted that the conversation about climate change can be abstract, with many dire statistics and sophisticated scientific models that can feel incomprehensible.

"Perhaps a monument to a lost glacier is a better way to fully grasp what we now face," she said, highlighting "the power of symbols and ceremony to provoke feelings".

‘Pretty visual’

Julien Weiss, an aerodynamics professor at the University of Berlin who attended Sunday’s ceremony with his wife and seven-year-old daughter, was one of those moved by seeing the ex-glacier Sunday.

"Seeing a glacier disappear is something you can feel, you can understand it and it’s pretty visual," he told AFP.

"You don’t feel climate change daily, it’s something that happens very slowly on a human scale, but very quickly on a geological scale."

Iceland loses about 11 billion tonnes of ice per year, and scientists fear all of the island’s 400-plus glaciers will be gone by 2200, according to Howe.

Glaciers cover about 11 percent of the country’s surface.

"A big part of our renewable energy is produced in the glacial rivers.... The disappearance of the glaciers will affect our energy system," Prime Minister Jakobsdottir said.

Stripped in 2014

Glaciologists stripped Okjokull of its glacier status in 2014, a first for Iceland.

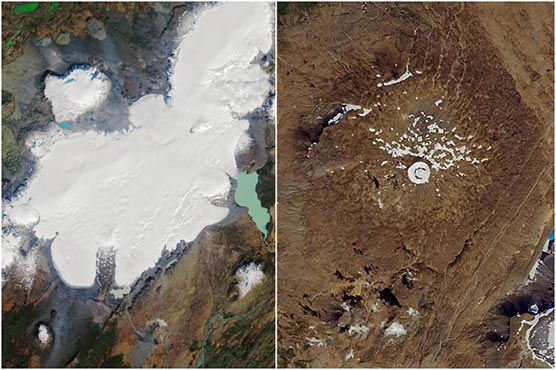

In 1890, the glacier ice covered 16 square kilometres (6.2 square miles) but by 2012, it measured just 0.7 square kilometres, according to a report from the University of Iceland from 2017.

In 2014, "we made the decision that this was no longer a living glacier, it was only dead ice, it was not moving," Oddur Sigurdsson, a glaciologist with the Icelandic Meteorological Office, told AFP.

To have the status of a glacier, the mass of ice and snow must be thick enough to move by its own weight. For that to happen the mass must be approximately 40 to 50 metres (130 to 165 feet) thick, he said.

According to a study published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)in April, nearly half of the world’s heritage sites could lose their glaciers by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions continue at the current rate.