Combating harassment on the streets

Recently women have begun being vocal about street harassment on social media

“At first I was scared and then I felt angry all the way back home. I was shaking with anger and disappointment. I wish I could’ve done more at that moment than just scream, but I couldn’t. No one around me tried to help. He ran away when I tried confronting him.”

Twenty-year-old Alina Ahmed was continuously cat-called at as she was walked from a Metro bus station to her Uber ride. Ahmed is just one of the many Pakistani women who have experienced public harassment at some point in their lives. In a public Facebook post, Ahmed shared her ordeal as well as why she had to post about it: “I’m done ignoring. I’m done not telling people about these things.”

Recently many women have become vocal about their harassment experiences on the streets and in public areas than ever before. Now they share their experiences everyday through the internet on different social media sites. Another woman had recently shared her story about harassment during a trip to the northern areas which went viral in Pakistan, stirring a heated debate about the presence and acceptance of women in public spaces.

The larger problem, however, is the acceptance of such a behavior which has lately begun being challenged by women.

Director of the Institute of Social and Cultural Studies (ISCS) at the University of the Punjab, Dr. Zakria Zakar explains the social reasons to why Pakistani culture allows such kind of a behavior. “Unfortunately this is our social psyche. If a boy behaves like a sexual deviant it is considered a normal behavior. There is a tolerance around this kind of act,” he says. “When they use foul language or behave in an indecent manner, people accept and it is considered very normal. We still lack basic decorum of public place decency.”

He says there are myths and stereotypes that are used to describe a woman in our society. “It is considered that women are by nature weak, they can’t keep secrets, they talk a lot etc. These things sow the seeds of harassment, because we have built up a mindset around this definition of women” he explains.

As long as this kind of stereotype remains in the definition of women, harassment will take place. He explains that despite public harassment being a global phenomenon, there is still some level of decency, especially in European countries where women can safely travel on buses and in public.

Although Pakistan is still a young country where there are countless social issues associated with women, there are some ground breaking changes that have been seen over the course of time. Women are trying to break the gender roles associated with them especially in urban centres, by leaving the confines of their homes and by commuting in public transports.

But while that phenomenon is taking place, waiting for a public transport or walking in public spaces also comes with its fair share of challenges. From slurs, sleazy remarks, catcalling from strangers passing by to even physical forms of harassment, women have faced it all.

Carol Brooks Gardner, author of Passing By: Gender and Public Harassment (1995) defines public harassment as: “…abuses, harryings, and annoyances characteristic of public places and uniquely facilitated by communication in public.” The definition goes on to add pinching, slapping, hitting, vulgarity, sly innuendos, ogling, and stalking.

Executive Director at HomeNet Pakistan Umme Laila Azhar has been working with the Government of Punjab to initiate projects that can help women to easily file complaints in a police station. She points out that the laws on harassment focus mostly on the workplace and there is greater awareness regarding it. “Although when it comes to street harassment it’s seen everywhere, on the streets, in public transport and bus stops. We tend to neglect women who are commuting on daily basis, not only in the urbanised areas but also in rural areas.”

“Working women face this kind of harassment on a daily basis; men who catcall and harass us do not understand that their one sentence can impact women in a negative manner,” she says. “In my monitoring and observation on this issue, I have seen that women have to take all this for no reason.”

Women are not complaining due to the social stigmas associated with the culture of feeling ashamed to file in a complaint against the accuser in police stations. For this Umme Laila is working hard with the government to provide women-assisted helpline desks in every station across the province. She adds to this, “but then again, women need that courage and confidence to go to a police station and report it. That is still absent from the picture.”

There are almost 700 help desks available to assist women in filing in a complaint, she claims. To a question about whether women go to police stations or seek help from the police she answers, “Sadly, they do not.”

Director of Bargad Organisation, Sabiha Shaheen is one of the few women who have been working for many years to sensitise men and women about harassment. According to her, working women face more harassment, especially while commuting, with people criticising her character, and colleagues watching them with suspicion.

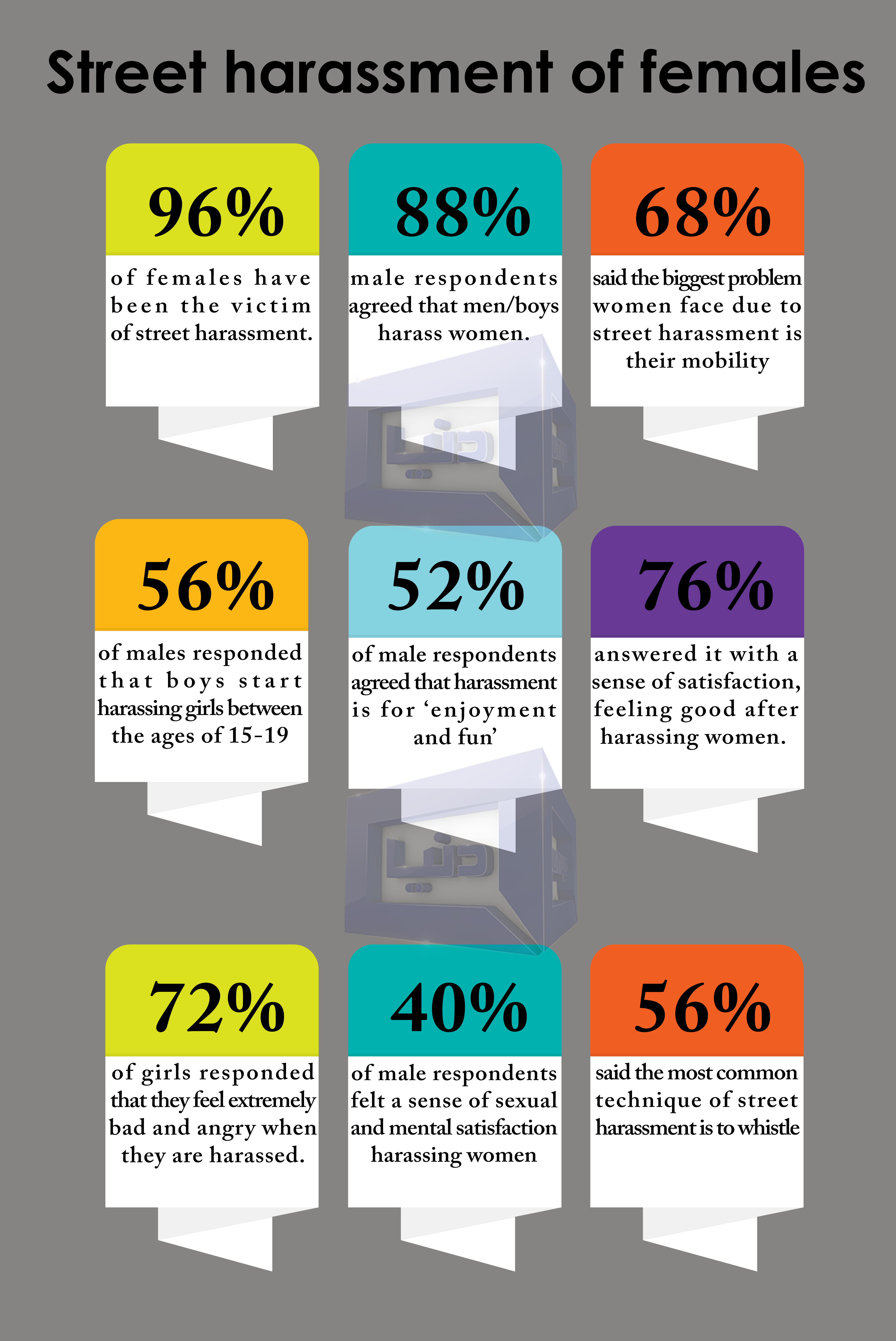

A research study on street harassment on girls was conducted in 2005 by Bargad funded by the Gender Equality Project (GEP) and supported by The British Council and the Department for International Development. The study which was focused in Gujranwala found that 96% of females have been the victim of street harassment while 88% male respondents agreed that men/boys harass women.

Study conducted by Bargad in 2005 about street harassment

Study conducted by Bargad in 2005 about street harassment

Around 76% of male respondents said that they felt a sense of satisfaction after harassing women and 52% of male respondents agreed that harassment is for ‘enjoyment and fun’. Around 72% of girls responded that they felt extremely bad and angry when they are harassed. Forty percent of men replied that they felt a sense of sexual and mental satisfaction harassing women on the streets.

The most common technique of street harassment is to whistle, according to the study. Almost 68% of female respondents said the biggest problem women face due to street harassment is their mobility.

While the study is almost a decade old, Shaheen’s work is now more focused towards generating awareness. “We must empower women. We need to stop the victim blaming,” she says. “If a woman is speaking about her experiences we should not put the blame on her or tell her it must have been her who provoked the men to harass in public,” Shaheen adds.

For the first time women safety audit tool has been launched by the Government of the Punjab which will try to assess women’s perceptions on safety especially in transportation facilities. The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) is trying to tackle harassment through technology. Women safety smartphone application was launched this year. The app has a panic button that connects the user to the police and emergency services through the phone number 15. Safe cities project is taking on different initiatives to bring forth the neglected issue of harassment of women in public places.

Umme Laila also sees hope with these initiatives in place including at transportation facilities and private cab services where awareness and sensitization programs are being put in place. “This kind of a mechanism is needed everywhere. They are aware of how to behave with a female customer, and if there is misbehavior on their behalf women can file in a complaint without any hesitation.”

But the issue is about the basics. “They don’t know how it feels when they are harassing or cat calling women. They have no idea how one word can impact a woman who’s merely commuting,” says Umme Laila.