Climbing athletes demand eating disorder action before Olympics

Sports

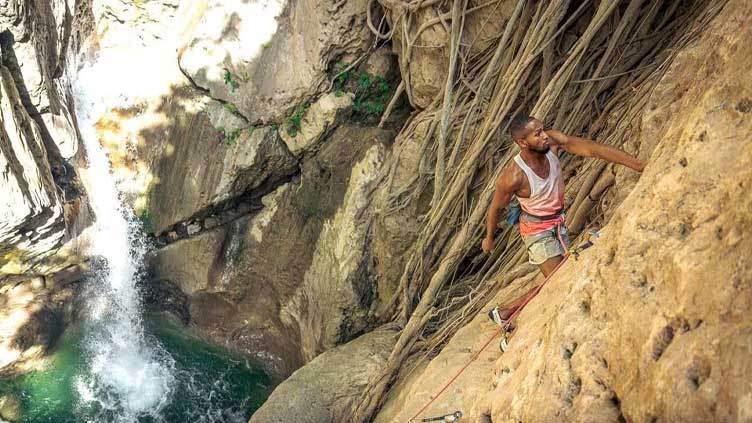

Lightner, now 24, is among a group of elite climbers speaking out about eating disorders

LONDON (Reuters) - Kai Lightner was a youth climbing world champion but after being told at 14 that his liver was close to failure and fracturing his spine in two places he realised the restrictions he put on eating to pursue success had spun dangerously out of control.

Lightner, now 24, is among a group of elite climbers speaking out about eating disorders and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), where athletes do not eat enough to fuel themselves.

They want the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) to stop unhealthy athletes competing - including at this year's Olympics in Paris which start in July.

"For many years, the IFSC would tell us that it was impossible for them to come up with any regulations from the legal side, that their solution was to leave it up to the national federations," said Jenya Kazbekova, a Ukrainian climber and member of the IFSC's advisory Athletes' Commission.

"National federations get funding and recognition only when they bring results and lots of organisations are concerned way more about the results than about the athletes," she said, adding that the commission had expressed concerns about climbers' health to IFSC management for years.

Stronger rules are being developed for 2024, IFSC President Marco Scolaris said. "I am convinced we will find a way to protect the athletes," he added.

DROPPING WEIGHT

As they fight gravity, climbers benefit from a higher strength-to-weight ratio. Many find losing weight easier than getting stronger, not realising the damage that can be done to their health. Lightner, tall for a climber at 6 foot 2 inches (1.88m), was told by coaches he had "junk in the trunk".

"For me, it was like, I can't control how tall I am but I can control how thin I am," he said.

Fellow U.S. climber Melina Costanza, 24, broke her foot in 2022 while training. She had eating disorders that compromised her bone density, after unintentionally losing weight during COVID lockdowns, noticing her performance initially improve as a result and then eating less.

While Lightner, who now climbs only outside, and Costanza, who won at the United States' 2023 nationals after a nutritionist helped change her relationship to food, were never diagnosed with RED-S, awareness of it is growing.

Recognised by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) as a syndrome in 2014, RED-S is caused by a prolonged, severe lack of energy, negatively affecting sports performance and health.

Symptoms can include low immunity, decreased bone density and disturbed sleep.

It is widespread in gymnastics, figure skating, artistic swimming, endurance and weight-class sports.

In a 2022 survey of 114 female sport climbers, 14.9% said they currently had an eating disorder, while 15.8% said they did not have periods, a common RED-S symptom.

'NEXT GENERATION'

The IFSC's voluntary Medical Commission had been measuring climbers' Body Mass Index (BMI) at least annually since 2012, according to former head Eugen Burtscher.

From 2017, BMI was used to flag athletes who could be dangerously underweight to their federations, but the IFSC did not stop anyone competing.

Frustration boiled over last year after the IFSC stopped measuring BMI at World Cups without any explanation. It was reintroduced later in 2023 after the outcry. "Climbing has a cultural and systemic weight problem," Canadian Olympian Alannah Yip wrote on Instagram.

Olympic gold medallist Janja Garnbret posted: "Do we want to raise the next generation of skeletons?," Burtscher and another doctor Volker Schoeffl resigned from the IFSC Medical Commission over the issue.

They said the Medical Commission suggested measuring BMI throughout 2023 to decide which athletes are screened for RED-S. Athletes requiring immediate treatment would have been prevented from competing.

Before the season, national federations had to measure athletes' BMI and provide further medical documentation for those below certain levels. The IFSC decided who could compete; no athletes were suspended, Scolaris said.

Schoeffl thought that was not enough, saying: "Pre-season screenings by national federations are not objective."

To protect athletes, any RED-S regulations need to withstand legal challenges, Scolaris said, adding that if the IFSC lost a court case it might have to shelve the policy for one to two years.

"Then we will (have to) authorise those who are unhealthy to compete."