Arabic calligraphy: ancient craft, modern art

LifeStyle

The art of Arabic calligraphy has been enhanced

(Web Desk) - The art of Arabic calligraphy has been enhanced and developed over the course of a millennia.

It has written the word of God, helped preserve human knowledge and understanding, and borne witness to the destruction of Baghdad. It has been codified, stylized, and lent itself to abstraction.

It has even struggled with the modern world and found renewed life in both art and typography.

Nowhere is calligraphy more revered than in Islam. According to Islamic tradition, God “taught with the pen, taught man that which he knew not” (Qur’an 96:4). No wonder the art of writing is both admired and cherished as a visual expression of faith.

Now it is being celebrated in all its forms, with Saudi Arabia extending the Year of Arabic Calligraphy into 2021 and UNESCO registering the art form on its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Arabic calligraphy is taking its rightful place at the heart of Arab identity. As the Iraqi calligrapher Wissam Shawkat says: “This is the one thing that is pure for us.”

On the banks of the Euphrates river, roughly 170 kilometers south of Baghdad, lies the Iraqi city of Kufa. Once renowned as a center of learning during the Islamic Golden Age, it has now been all but consumed by Najaf.

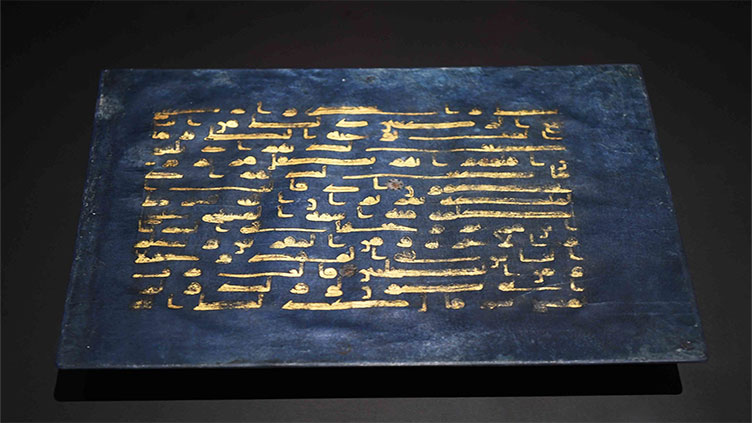

Kufa is the city that gave its name to Kufic, the earliest example of a universal calligraphic style and a favored script for transcription of the Holy Qur’an. Many of the earliest extant copies of the Islamic holy book, including the Blue Qur’an — a 9th-century manuscript believed to have been produced in Spain — and the Topkapi manuscript, the oldest near-complete Qur’an in existence, were written using this foundational script.

Kufic’s geometric elegance also meant it was well suited to architectural decoration, with one of its earliest known examples found in a 240-meter-long Qur’anic inscription inside Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock.

The oldest, however, dates from 644 CE and is engraved on a rock near AlUla in Saudi Arabia, according to the Kingdom’s submission to UNESCO’s Memory of the World register. Known as The Inscription of Zuhayr, it is situated on an ancient trade and pilgrimage route between Al-Mabiyat and Madain Saleh and states the date of death of Umar Ibn Al-Khattab, the second Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate.

However, the exact origins of Kufic and the scripts that preceded it are unclear. The Arabic alphabet is believed to have evolved from Nabataean, an Aramaic dialect used by a semi-nomadic Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia, the southern Levant and the Sinai Peninsula from around the 4th century BCE.

Today, the Nabataeans are best known for the architectural wonders they bequeathed the world, including Petra in Jordan and Madain Saleh in Saudi Arabia. What is less appreciated is their pivotal role in the formation of the Arabic script.

The Nabateans used a form of writing that flowed from right to left and had strong similarities with Arabic, including its cursive nature and its reliance on bodies of text that consisted largely of consonants and long vowels.

How Nabataean evolved into Arabic is not precisely clear, but in 2014 a joint Saudi-French archaeological team discovered what is, at present, the oldest known inscription in the Arabic alphabet. Dating from 469 to 470 CE, it was found 100 kilometers north of Najran in Saudi Arabia and is written in a mixed text known as Nabataean Arabic.

The discovery, described at the time as the ‘missing link’ between Nabataean and Arabic writing, helps explain why Nabataean is considered the direct precursor to the Arabic script. Prior to this, the earliest extant Arabic inscription was from Namara in modern day Syria (dating from 328 CE), but it is written solely in Nabataean characters.

The earliest form of Arabic script is known as Jazm, which in turn developed into a number of differing styles, including Hiri, Anbari, Makki and Madani.

These styles were named after the cities or regions from which they emerged (for example, Makki and Madani were from Makkah and Madinah respectively) and were particular to their time and location. Madani and Makki are also linked together under Hijazi, the collective name for a number of scripts from the Hijaz region. Ma’il, another Hijazi script used in a number of the earliest Qur’anic manuscripts, is believed to be the direct predecessor of Kufic. The so-called "Birmingham Qur'an," from the 7th century CE, is a wonderful, albeit incomplete, example of the Hijazi style.