Read my mind: French researchers building world's most powerful MRI scanner

The giant magnet could help better diagnose maladies such as Alzheimer�s disease, the team says.

SACLAY/LONDON (Reuters) - Researchers in France are developing an MRI scanner using a supermagnet that would produce brain imaging of a much higher resolution, and could better explain neurological functions and detect illnesses at their onset.

The giant magnet, which is being developed through Project Iseult at the Neurospin facility near Paris, could help better diagnose maladies such as Alzheimer’s disease, the team says.

"We hope that this magnet would allow us... to better understand our brain and how it works, and to study characteristics of what is special to the human species, things like music, mathematics and language," Project Iseult Scientific Director Nicolas Boulant told Reuters on Tuesday (September 17).

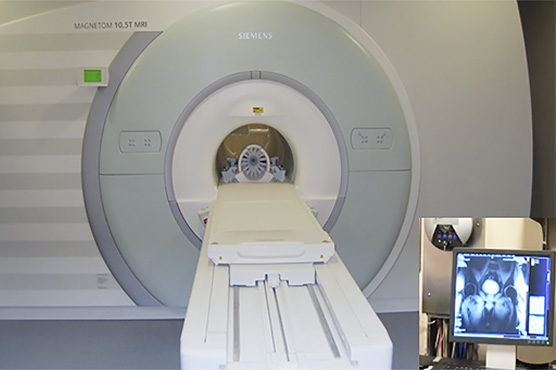

Magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images from inside the body.

Project Iseult’s new supermagnet measures 5 metres in length and 5 metres (16ft.) in diameter, about as long as a sedan, and weighs 130 metric tonnes, the weight of a blue whale. It is built by layering 170 "double pancake" superconductor coils of niobium-titanium alloy. A total of 182 kilometres (113 miles) of wire made of the alloy were used for the magnet.

The apparatus emits a magnetic field of 11.7 Teslas; 230,000 times stronger than the Earth’s, the project’s magnet engineer Lionel Quettier said.

Once in place, the Iseult could produce images 10 times clearer than those obtained with today’s most advanced MRI machine, which has a magnetic field of 7 Teslas. Classic hospital MRI machines emit 1 to 3 Teslas of magnetic field.

But Quettier said Iseult’s machine would not be ready for at least another year. Project engineers are currently conducting tests on the magnet, but the main part of the development would start in early 2020, when the apparatus would be examined with actual MRI equipment.

"Then, we’ll redo the same tests that we are currently conducting, and by late 2020 or around 2021, we’ll have our first image," Quettier said.