Istanbul Biennial gives artists political voice

As journalists are arrested and democracy diminishes in Turkey, the Istanbul Biennial and Contemporary Istanbul art events won't be pulling any political punches. Photo: Lungiswa Gqunta

While a trailer for the Istanbul Biennial presents idyllic images of the Bosphorus strait, potential visitors to events at Istanbul Art Week, the largest art showcase ever seen in Turkey, will be questioning their participation amid arrests, repression and a broader government crackdown against opposition in the country.

Nonetheless, a trip to Turkey for the Istanbul Biennial (September 16 - November 12), which follows on from Contemporary Istanbul (September 14 - 17), will reveal art that speaks a subtle but clear political language, and that sends a message to the Turkish government. Indeed, this could be the most important political moment in Turkish art since the Gezi protests of 2013.

#istanbulbienali#kocholding pic.twitter.com/LsoWXgjM03

— İstanbul Bienali (@istanbulbienali) September 14, 2017

Political messaging

In a nearly 600-year-old hammam in the Islamic district of Fatih, on the Golden Horn of Istanbul, the artist Monica Bonvicini created one of the most unusual works of the Biennial: a replica of the Kaaba, the most holy site in Islam, made up of black belts organised into a cube.

Fifty-six artists from 32 countries have contributed to this year’s Istanbul Biennial, which is curated by the Danish-Norwegian artist duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset. This year’s title, "a good neighbor," is surely evocative – yet ambiguous. Is it asking whether Turkey is a good neighbor?

"None of the artists invited by us criticises directly the political events of the last year," Dragset told DW. "They are quiet voices. The artists want to get together, find new strength and represent an opposing attitude. This happens not boldly but rather more indirectly, in a poetic language. But the exhibition gives a very different picture from what the government would like to see."

Artist duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset are curating an Istanbul Biennial with inevitable political overtones. Photo: DW

Addressing the migrant crisis

With 3.5 million refugees housed in Turkey under an EU agreement, it is not surprising that refugees and migrants comprise the dominant theme at the Istanbul Biennial.

"We had not planned this in any way," said Ingar Dragset. Nonetheless, the theme obviously inspired some of the strongest works at the event.

Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed, for example, has created a statue (controversially) made of ivory to recreate the famous "Napalm Girl" photo from 1967 that shows a screaming Vietnamese girl fleeing a village that has been bombed with napalm. Bizarrely, the naked girl in Abdessemed’s "Cri" resembles a ballet dancer who is using her arms like wings.

.jpg)

Adel Abdessemed recreated the famous picture of Vietnamese girl fleeing a village that has been bombed with napalm in 1986, Cri, 2013, Ivory. Photo: Sahir Ugur Eren

The Turkish artist Volkan Aslan presents a video, "Home Sweet Home," in which two women peacefully pot flowers, drink coffee and lie in bed - but the viewer ultimately realises they are chugging along the Bosphorus on a houseboat and face an uncertain future as they look for a new home.

Born in Baghdad in 1966, Iraqi-Canadian artist Mahmoud Obaidi contributes paintings created on unstable plaster that also incorporate early childhood drawings. Among them, "Make War not Love" tells of the experience of violence and homelessness.

"Home Sweet Home" reflects on the migrant crisis in Turkey. Photo: DW

Olaf Metzel has recycled one of his earlier works, "Sammelstelle," a closed room made of sheet metal and aluminum that originally portrayed the claustrophobic transit areas created for refugees from the former Yugoslavia in 1992. Here, the concept gains revived import in light of the contemporary refugee crisis.

Inspired by hell

Gloomy political messages can also be found at the Contemporary Istanbul art fair, which is taking place for the first time parallel to the Istanbul Biennial.

"My work is inspired by hell, but also by Dante s Inferno," said Erkut Terliksiz from the gallery x-ist. "I used to paint in brighter colors, but the atmosphere in our country has become apocalyptic," he added. Amid stars raining from heaven, Terliksiz painted a donkey feverishly working on the salvation of the world in a kind of laboratory. But can a donkey save the world?

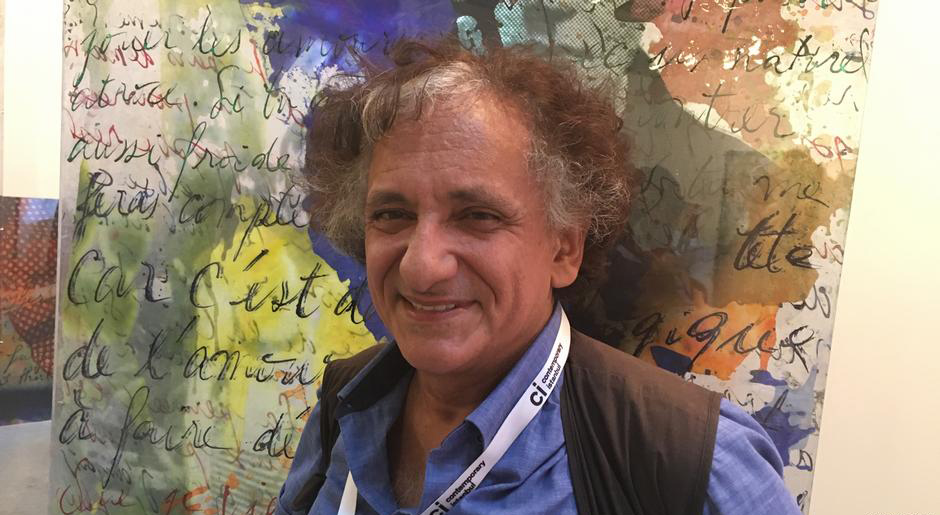

Artist Bedri Baykam, the battle-hardened enfant terrible of the Turkish culture scene, has made it his mission to rescue Turkish democracy at Contemporary Istanbul.

President of both the Turkish artists association and the UNESCO International Association of Art, he is full of indignation at the withering of democracy in his country. In response, he has recreated the "Democracy Box," a telephone booth within which people can do, or come and go, as they please.

Bedri Baykam wants to preserve a single square meter of freedom with his "Democracy Box". Photo: DW

"This is a square meter of freedom," said Baykam.

"There are ... couples who have entered and have made love. [It s a] free space where you can do what you want." In 1987, the "Democracy Box" was shown for the first time in Istanbul at the Atatürk Cultural Center, and is now on sale for 500,000 dollars (418,500 euros). The sale aims to help preserve a piece of Turkish democracy.

The story originally appeared in DW.